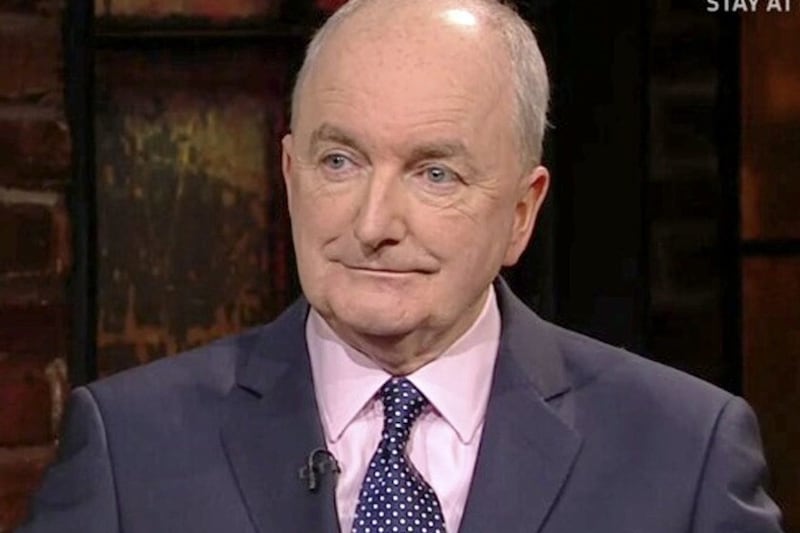

The history of the Irish Republican Brotherhood is a hidden history, buried within the political and military chronology of the time. In his new book, The Irish Republican Brotherhood 1914-1924, John O’Beirne Ranelagh lifts the veil on the story of the IRB during the most critical phase of its campaign for Irish independence. With a father who was a member of the IRB and took part in the Easter Rising, War of Independence and the Civil War as an anti-Treaty officer, Ranelagh has had unique access to those who populated its ranks, many of whom refused to be interviewed by anyone else. Using personal testimonies from almost 100 key figures he interviewed, including Éamon de Valera, Sheila Humphries, Emmet Dalton, Todd Andrews, Vinnie Byrne and Moss Twomey, as well as new archival material, Ranelagh unravels the true influence of the organisation to which Michael Collins pledged his foremost loyalty. In this extract, the author sets the scene and gives an overview of the IRB’s influence.

****

THE intricate tapestry of the 1914-24 period begins with the origins of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and Theobald Wolfe Tone (1763–98). Tone was a leader of the 1798 Irish rebellion, the most serious rebellion in Ireland since 1641, with France as an ally. A member of the Church of Ireland, he was inspired by the American and French Revolutions, and was motivated by the condition of the impoverished Catholic Irish. Tone believed that only violence would expel England from Ireland. He influenced all future Irish revolutionaries and is venerated by republicans to the present day.

Tone represented political non-sectarian nationalism, which is always open to compromise. Irish Catholic nationalism was cultural and thus more absolute. The IRB, however, like Tone, was not sectarian. Indeed, several of its leaders were Protestants. The men and women of 1916 fought for an idea of Irish culture that they saw fading in the face of an anglophone cultural, economic and political attack.

At all times the IRB concentrated on influencing cultural organisations. It dismissed the Irish Parliamentary Party as craven at the feet of England – of “the foreigner”. For the IRB, cultural nationality was paramount.

The IRB was created in 1858 and was at first known as the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood. Its goal was complete Irish independence. It named its membership ‘circles’ – its basic organisational unit – after leaders of the 1798 rebellion. In 1964 the IRB’s remaining funds paid in part for Tone’s statue, sculpted and cast by Edward Delaney and erected in St Stephen’s Green in a granite monolith setting designed by Noel Keating and unveiled on November 18 1967 by President de Valera. Tone was the IRB’s inspiration and he also marked its end.

The IRB had international reach and membership: the Irish diaspora was substantial within the British Empire, South America and the United States. From its formation in 1858 until 1922 it maintained an identity separate from all other organisations, although during 1920-21 passively within the IRA.

The IRB’s leaders did not really think of being the government of an Irish state. They thought of themselves as awakeners of the oppressed nation whose language and culture had been destroyed by England

It was intellectually substantial. It thought beyond blood and excitement. It was an organisation designed to expend itself in rebellion, not to live forever. It wanted to establish a state governed by Irishmen and prosperous in the long term. Italy and Greece had been established in the nineteenth century by the determination of a handful of people in secret societies: the IRB positioned itself to achieve the same for Ireland.

Its leaders did not really think of being the government of an Irish state. They thought of themselves as awakeners of the oppressed nation whose language and culture had been destroyed by England.

They also thought that the Church had been won over to side with Britain. The Church, itself an imperial organisation, understood that Ireland within the United Kingdom gave it influence within the British Empire, principally through Irish MPs: it was not surprising that the Church generally sided with the government in Ireland and condemned membership of a secret society – the IRB – as sinful. In 1919, for example, a priest who gave evidence in court on behalf of a Volunteer/IRA man was transferred within a week to the United States.

Larry de Lacey, a journalist member, saw the IRB as a driving force: “It was that curious live core; it was the power cell. Because the people that were in it were of a pretty good standard... But there were a good many very able men, and there were men with influence in queer, far-reaching ways: very important. They were influencing public bodies; they were preventing votes of flattery to the Queen and the King; they were preventing this, that and the other.”

The IRB voiced liberal generalisations but was not really interested in social issues. In October 1865 a Ladies’ Committee was established, mainly by wives and relatives of IRB leaders, to support IRB prisoners’ families. Yet in the twentieth century only three women, Maud Gonne MacBride, Geraldine Plunkett and Úna Brennan, were ever members of the IRB itself.

From 1873 it had a constitution that through omission made its lack of interest in social matters clear. Being Irish was its entry requirement, as clause 1 of the constitution stated: “The IRB is and shall be composed of Irishmen, irrespective of class or creed resident in Ireland, England, Scotland, America, Australia, and in all other lands where Irishmen live, who are willing to labour for the establishment of a free and independent Republican Government in Ireland.”

In common with many secret societies, the IRB’s existence was known from its start; exactly what it was doing was unknown until it burst out in revolt. But there was no secret about its objective, its nature or its leaders, all of whom were known to the Dublin Metropolitan Police and the RIC.

They were rebels and terrorists. Such people are conspiratorial and invariably have a simple black and white view of the world, often sustained by historical misrepresentation. Terror and rebellion were the IRB’s defining elements and, through the IRA, its legacy to modern Ireland.

Secret societies protect themselves with conspiracies underpinned with deceit and propaganda. They also have a mystique that can attract members and may have objectives that are attractive too.

We knew the IRB was the highest thing behind the actions of the IRA and I considered that unless I was a member of the IRB I couldn’t consider myself a real republican soldier

— Patrick Mullaney, Co Kildare IRB leader

They use initiation ceremonies as an entry point to a belief system with the comradeship and exclusivity of membership acting as powerful attractions. A formal oath-taking was the IRB’s ceremony. When rebellions are the purpose of these societies, fear is added to the mix: rebellions are intended to be unnoticed until unleashed and so call forth murderous policing of secrecy. Revolutionary conspirators are imprisoned by the deceits that also protect them: self-delusion is a necessity as they prepare to kill and to die for their cause.

Ignorance and secrecy were intended within the IRB. It did not have mechanisms for feedback from below. It did not want debate. This was a reaction to an overwhelming enemy presence: only an extreme organisation could make itself felt. Its leaders thought – wrongly as 1916 demonstrated – that a suicide charge would inflame Ireland; that in the long term they would achieve a united, armed independent country that would ally with Britain’s many enemies.

The IRB was not a force for democracy (although democracy and violence are not mutually exclusive), and its members did not respect democracy. Identifying men of ability with strong nationalist feelings and binding them to fight for an independent republic was its modus vivendi. “They were the ‘saved’,” said Joe O’Doherty, “and they were going to see that everybody was in line with their idea of salvation.”

Infiltration of nationalist bodies, exercising influence rather than command and control, was its modus operandi. Thomas Malone, in the IRB from 1914, observed: “On the quiet, when it was a question of some one fellow instead of another fellow being put in as O/C or something or other, the IRB influence was used.”

It was a doorway to what the IRB termed “physical force” that, once taken, saw its members absorbed by the Volunteers/IRA after 1919. Tom McEllistrim, Vice-O/C Volunteer/IRA Second Kerry Brigade, put it simply: “The Volunteers ate up the IRB.”

Looking back in 1973, Tom Maguire, a senior IRB member and O/C Volunteer/IRA Second Western Division in 1921, saw the IRB as the guardian of Irish republicanism: “If everybody else failed the IRB would hold for the republican tradition.”

Patrick Mullaney, the Co Kildare IRB leader, was definite: “We knew the IRB was the highest thing behind the actions of the IRA and I considered that unless I was a member of the IRB I couldn’t consider myself a real republican soldier.”